About the Artwork

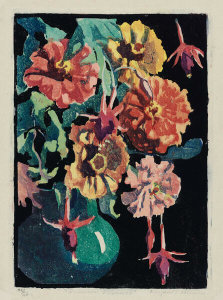

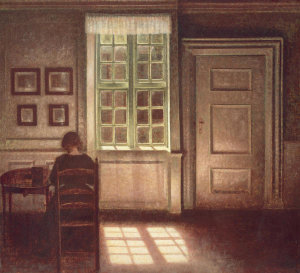

Sheeler, an avant-garde painter and photographer during the first half of the twentieth century, is best-known for his crisp, meticulous paintings of industrial or man-made subjects. But he also rendered rural landscapes and barns, still lifes, and starting in 1919, domestic interiors, a motif that became one of his major themes. Sheeler settled with his wife, Katharine, in the rural community of South Salem, New York in 1926, furnishing his new home-a “bungalow-like building”-with the early American antiques that he had been collecting since the mid-1910s. Shortly thereafter, he began work on three large still life compositions, one in tempera and two in oil, all of which develop an innovative formula of still lifes situated within a domestic setting, a theme he had introduced in his painting Interior (1926, Whitney Museum of American Art). The mood of these pictures is cheerful; one can imagine they reflect Sheeler’s feelings of optimism and well-being. The arrangement of forms seems conventional and the objects depicted are familiar and ordinary: forsythia, and Sheeler’s often-used candle stand and a glass mug. The architectural features in the background are undoubtedly those of Sheeler’s house in South Salem. In spite of the familiar subjects, however, the canvases are experimental in the variety of painting techniques Sheeler employed. In Spring Interior, the shimmering opalescent backdrop is thinly painted, with virtually no sign of brush stroke, while the mantelpiece, rendered in the same tones, is thick and creamy. The stems of the forsythia, refracted through water and glass, are rendered with coloristic complexity. The petals are richly painted, each described by a single deft, lean stroke, while the bricks above the mantel are rendered with pigment so thinned down as to resemble watercolor; the mortar between the bricks is defined by pencil underdrawing and bare canvas. It is as though Sheeler were pushing the medium of oil paint in several directions in order to achieve as many different effects and surface textures as he could.

Sheeler’s obvious pleasure in painting beloved objects in new surroundings and his interest in his medium were matched by his enjoyment in the manipulation of space. “Spring Interior” is more complex than it seems at first glance. The branches of forsythia form a screen before a delightfully confounding series of optical illusions. At right, the series of moldings that ornament the mantelpiece seem at once to undulate and to project progressively into space as the eye moves away from the hearth. And at left, the wall recedes into space at the bottom, suggesting stairs or bookshelves, while at the top the same horizontal slats from part of pattern of flat bands decorating a wall that is flush with the mantel. The illusion of recession is contradicted by the shaft of the candle stand, which shares an outline with the mantel, so they appear to be simultaneously side by side and before and behind. These ambiguities, these disjunctions between what the eye sees and what the mind records, take on a more unsettling, somber quality in later works. Here, in keeping with the sunny palette and the pleasant, everyday objects, the effect is coy and playful.