Art Categories

- Artists by Category

- American Artists

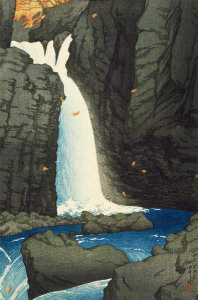

- Asian Artists

- European Artists

- Old Masters

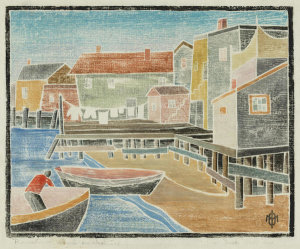

- New England Artists

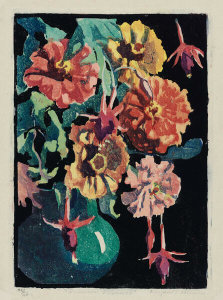

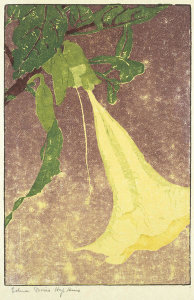

- Women Artists

- Art by Time Period

- 21st century

- 20th century

- 19th century

- 18th century

- 17th century

- 16th century

- 15th century

Individually made-to-order for shipping within 10 business days

Subjects

- People & Activities

- Portraits

- Leisure

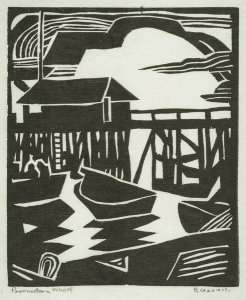

- Boats and Ships

- Sports

- Music

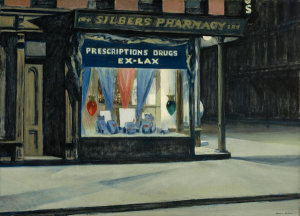

- Interiors

- Fashion

- Literary

- Religion and Spirituality

- Art Mediums

- Paintings

- Scrolls

- Prints

- Vintage Posters

- Pastels

- Watercolors

Your Custom Prints order supports the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Most Popular

- Popular Collections

- Japanese Prints

- Impressionism in Europe

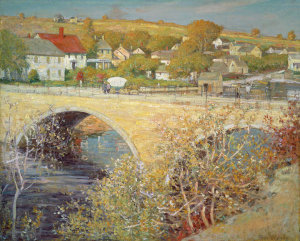

- Impressionism in America

- Watercolors

- Pastel Drawings

Prints and framing handmade to order in the USA

![Kawase Hasui - Evening Snow at Edogawa (Kure no yuki [Edogawa]), 1932](/vitruvius/render/300/476788.jpg)